Artist: Idris Khan

Edition size: 2 + 1 Artist’s proof

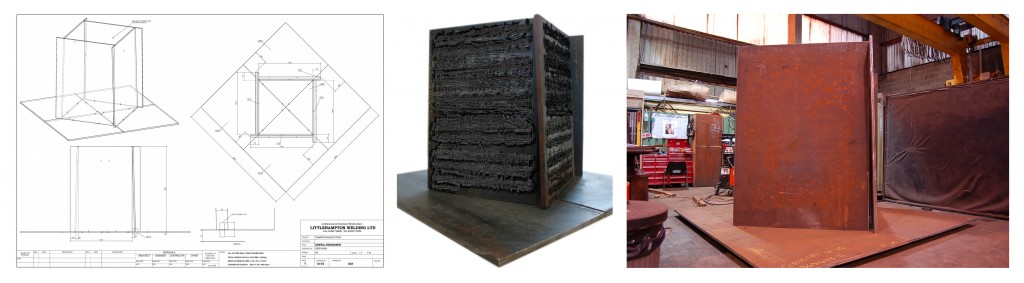

Fabrication: Littlehampton Welding

Installation: MTEC Group / Tom Colebrook

Structural engineers: Littlehampton Welding

Time frame: Summer 2008 – Early 2009

Funding: Yvon Lambert Gallery, Yarat Contemporary Art Space

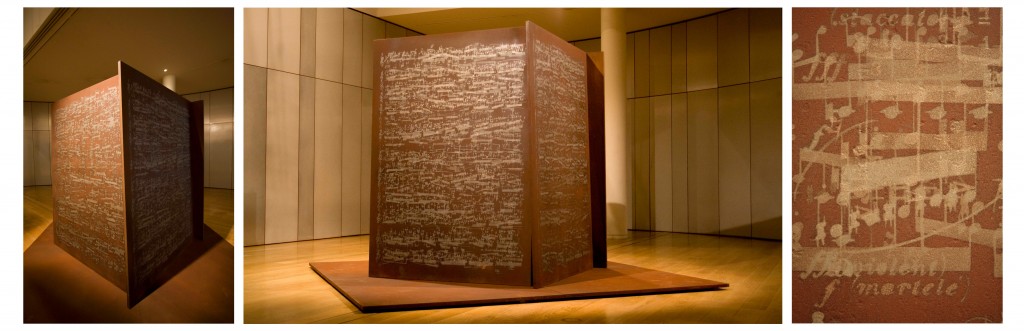

This was the first three-dimensional work that Idris Khan and I worked on, it was a new move for the artist insomuch as it marked his first departure from the realm of photography. It was a gateway project, with a long time spent in the design and pre-production phases; we developed techniques and practices that would be utilised in the execution new sculptural works to come. It was also through this work that we cemented long lasting working relationships with both Littlehampton Welding – a structural metal works on the south coast and Graham Dann, a bespoke sandblaster.

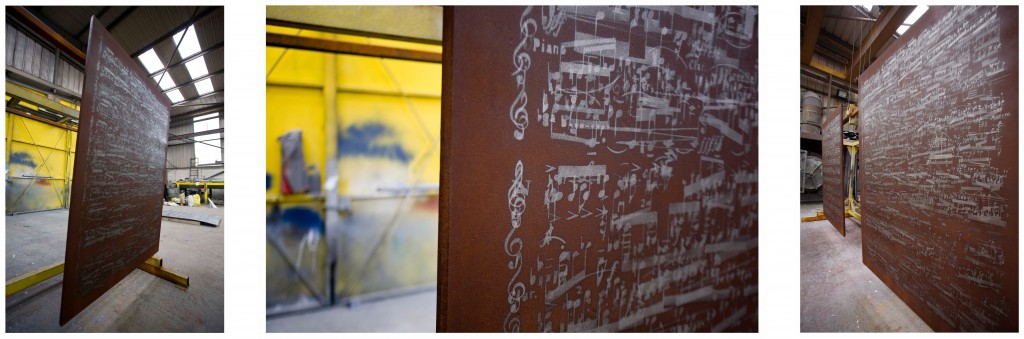

Idris’s concept was seemingly straight forward; to translate in to physical marks, the richly layered surfaces he had been achieving within his photographic works. In essence it was to re-address the notion of the indexical – the physical presence of the mark-as-record, as trace, one that up until now had remained easily and neatly contained within the frame of the image. The challenge was just this, presenting the mark upon the dense surface of steel whilst maintaining the subtlety of graduation, of translucency, achieving a sculptural image that retained the recessive nature of his photographic images.

The piece takes its name – ‘Quartet for the end of time’ , from a musical arrangement composed by Olivier Messiaen. A haunting and disjointed work, that echoes his time spent within the terrifying confinement of the concentration camp. It was believed that in desperation he inscribed much of the musical composition directly on to the walls of his cell, an indexical act of absolute need in itself. The sculpture was intended to be included within a show of works – put together by the Yvon Lambert gallery – dedicated to the late composer, and whilst it was eventually replaced by a larger photographic work of the same theme, it nevertheless remains as considered and technically astute monument. The layered marks that penetrate the steel surface hold within them a history and an age; emerging from the rust they feel preserved and protected, poignantly echoing the determined acts of the composer himself.

The design of the sculpture was loosely influenced by an early work of Richard Serra, One Tonne Prop, in which Serra arranged four slabs of lead in a self-supporting arrangement, resembling the basic initial formation of a house of cards. The change in size of the plates was specific, it being critical that the height and width ratio of the musical sheet was maintained. In height the plates measure to just below 2 metres, allowing for a form that remains just beyond the scale of the viewer, yet it doesn’t overcome us. The working drawings were generated and fabrication undertaken by Littlehampton Welding; four, 25mm thick steel panels with a pre determined orientation sit upon square base plates, recessed holes within the steel allow for a registration and fixing with use of high tensile stainless steel dowels. To achieve a uniform rusted surface, all steel elements were shot blasted and left to rust outside with the help of a daily salted water spray.

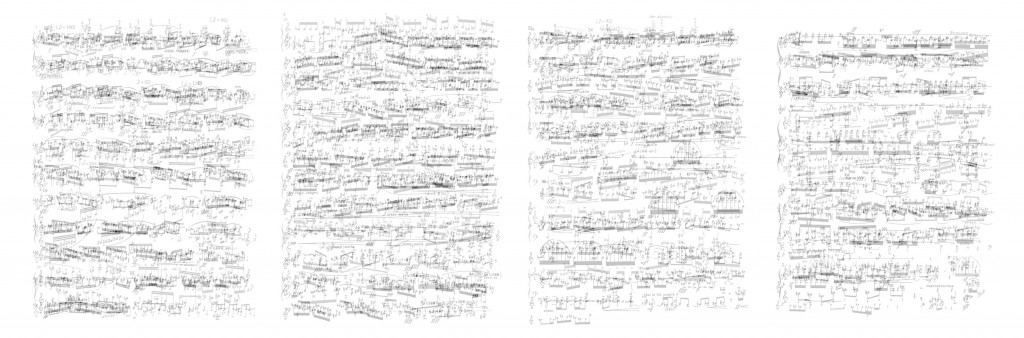

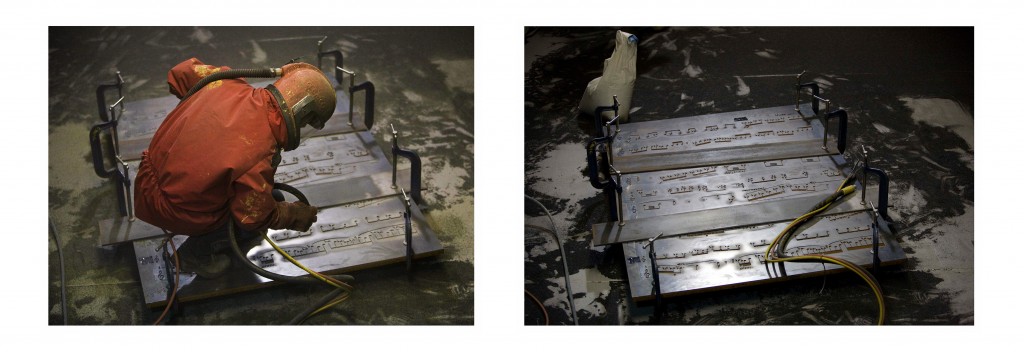

The initial production phase within the studio involved developing a technique that would allow for the translation of musical notes – in their notated form – into shapes that we could work with on physical and sculptural platform. This aspect of the work was two-phase. Firstly –digitally orientated, with the literal extraction of the notes from the printed page, via high resolution scanning, and secondly – to decide upon the technique needed to achieve the literal ‘imprint’ on to the steel surface. Working with Graham Dann on a series of sandblasted tests, we established that with careful manipulation of pressure and the use of variating strengths of grits fired at high pressure on to the steel surface, different levels of texture and opacity could be achieved. By creating templates or stencils we could generate the negative form of the note, and blasting through this, the shape of the note would be achieved. The artist’s decision was to allocate each of the four plates its own instrument, corresponding to those used in the composition: Cello, Violin, Piano and Clarinet. Four sheets of each – totalling sixteen, would need to be extracted and converted into template form. The lengthy process of digitally removing each individual note from the staves, a cross platform digital work path could be outputted to CAD files, which in turn would be laser cut from a 2mm rolled steel sheet.

The creation of the sandblasted musical layers and finishing of the plates was conducted at Littlehampton Welding. Working with a plate at a time, each sheet of music in negative template form was allocated a particular type of grit, and with careful blasting the required level of depth and opacity was created. The precision and sensitivity of the result is extraordinary, all the inherent aggression and force of the sandblasting technique is all but lost in the final finish. With the decision to leave the exposed steel to very subtly rust for a few days before applying the finish oil based laqcuer, the feeling is that these layered marks are the result of a lengthy etch, a gradual eating away at the surface, decidedly temporal, something that has evolved rather than something immediate. Sandblasting is a process mostly associated with uniformity, with stripping away and removing, here it is used to build and to layer, implying many depths within one surface. The once impenetrable and staunch steel slabs are finally given a lyricism, the plates become tablets ascribed with a permanent musical resonance, contemplative and evocative.

We made two editions of this work and I have installed the piece twice, early in 2009 in Paris at L’Espace Luis Vuitton with the aid of MTEC group, and again in 2012 at the Yarat space for Contemporary Art in Baku, Azerbaijan. It’s a cumbersome work weighing almost 3 tonnes in total, so the process is slow and the use of a gantry assembly essential. The simplicity of the design however makes for a very fluid arrangement, assembling first the four floor-base sections then working your way around the upper plates, finally popping in the last section in under tension with the use of a strong ratchet.

I thank Idris khan for the vision, Littlehampton Welding for their speed and professional fabrication and Graham Dann for his lightness of touch with the sandblasting equipment. This is a work that came together with little problem, and it will always remain one of my most loved sculptures we’ve worked on together.

Photography © Tom Colebrook 2009 /Artworks © Idris Khan 2009